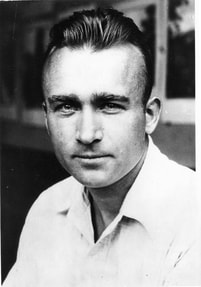

In 1929, the Pennsylvanians were suddenly visited by a force of nature. His name was Myron Avery. Avery radiated a unique manic energy that took the trail builders in the Quaker State by surprise.

Myron Avery, a young lawyer, had come from Maine by way of Harvard Law School. He arrived in Washington D.C. around 1926 (we are not sure of the date), and quickly appeared on the local hiking scene. It was said that no one could hike as fast as Avery.

In 1927 he became one of the six founders of the new Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), and began scouting the route of the A.T. southwest of Duncannon. He was joined in this by one Frank Schairer, a recent Yale graduate. Those who encountered Schairer were overwhelmed by his enthusiasm. With Schairer, Avery now had the perfect trail companion.

Myron Avery, a young lawyer, had come from Maine by way of Harvard Law School. He arrived in Washington D.C. around 1926 (we are not sure of the date), and quickly appeared on the local hiking scene. It was said that no one could hike as fast as Avery.

In 1927 he became one of the six founders of the new Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), and began scouting the route of the A.T. southwest of Duncannon. He was joined in this by one Frank Schairer, a recent Yale graduate. Those who encountered Schairer were overwhelmed by his enthusiasm. With Schairer, Avery now had the perfect trail companion.

Myron Avery

Avery (center), Frank Shairer (right) and an unknown companion, on Katahdin

The Pennsylvanians originally planned a route for the AT on Blue Mountain from Delaware Water Gap at the Pennsylvania-New Jersey line, all the way to the Potomac River. That route would have avoided Cumberland Valley, with its houses and farms, staying on the ridges north of the valley – Blue Mountain, Rising Mountain, Tuscarora Mountain. Much of it was private land at the time, although Pennsylvania was creating state game land and forests at a remarkable rate.

Avery looked at the plans, and rejected them. In 1929, he wrote to Arthur Perkins, the chairman of the board of managers of ATC, that he intended to put the trail across Cumberland Valley, and into Michaux State Forest, and Perkins approved. Avery turned the trail into the valley at Lambs Gap on the Darlington Trail. Wasting no time, he and Schairer painted blazes on roads across the valley (some are still visible) to a route that is no longer part of the AT. (Today it is called the White Rocks Trail.)

Avery looked at the plans, and rejected them. In 1929, he wrote to Arthur Perkins, the chairman of the board of managers of ATC, that he intended to put the trail across Cumberland Valley, and into Michaux State Forest, and Perkins approved. Avery turned the trail into the valley at Lambs Gap on the Darlington Trail. Wasting no time, he and Schairer painted blazes on roads across the valley (some are still visible) to a route that is no longer part of the AT. (Today it is called the White Rocks Trail.)

Arthur Perkins

Coming to the top of the ridge, it turned toward Pine Grove Furnace, an iron smelting works that had been closed in 1874 after a century of operation. A state park had opened there in 1921. To Avery’s idea, the trail should continue on through the states forest, all the way to the Pen Mar Park on the Maryland-Pennsylvania line. A popular tourist destination, it, too, would be an ideal place for the trail.

Avery found colleagues in the state forests. He formed a bond with forester Tom Norris of Mont Alto and Tom Bradley of Michaux. The foresters suggested a preliminary route using old roads. The irrepressible Avery was out on the suggested route, accompanied by Schairer, almost immediately, hiking Pen Mar to a point just north of the Big Flat fire tower. “We were extremely pleased with the route selected. It is Appalachian Trail caliber in every way,” Avery wrote to Bradley.”[1]

The official route through the two forests was marked by two parties of state foresters, in February of 1931. One group began walking north and the other walked south. Later in the month, a bus load of 45 enthusiastic PATC members invaded Mont Alto Forest to walk 12 miles of the new trail, led by Tom Bradley.[2] The interaction between PATC and the two groups of foresters was very smooth, and before the end of 1931, there was an established route of the A.T. all the way across Pennsylvania. It was one of Avery’s most successful and enduring partnerships, probably because he let the public officials lead.

[1] Avery to T. G. Norris of Michaux, Dec 23, 1930. White blazes can still be seem along the old route.

[2] Gettysburg Star Sentinel, Mar 14, 1931.

Coming to the top of the ridge, it turned toward Pine Grove Furnace, an iron smelting works that had been closed in 1874 after a century of operation. A state park had opened there in 1921. To Avery’s idea, the trail should continue on through the states forest, all the way to the Pen Mar Park on the Maryland-Pennsylvania line. A popular tourist destination, it, too, would be an ideal place for the trail.

Avery found colleagues in the state forests. He formed a bond with forester Tom Norris of Mont Alto and Tom Bradley of Michaux. The foresters suggested a preliminary route using old roads. The irrepressible Avery was out on the suggested route, accompanied by Schairer, almost immediately, hiking Pen Mar to a point just north of the Big Flat fire tower. “We were extremely pleased with the route selected. It is Appalachian Trail caliber in every way,” Avery wrote to Bradley.”[1]

The official route through the two forests was marked by two parties of state foresters, in February of 1931. One group began walking north and the other walked south. Later in the month, a bus load of 45 enthusiastic PATC members invaded Mont Alto Forest to walk 12 miles of the new trail, led by Tom Bradley.[2] The interaction between PATC and the two groups of foresters was very smooth, and before the end of 1931, there was an established route of the A.T. all the way across Pennsylvania. It was one of Avery’s most successful and enduring partnerships, probably because he let the public officials lead.

[1] Avery to T. G. Norris of Michaux, Dec 23, 1930. White blazes can still be seem along the old route.

[2] Gettysburg Star Sentinel, Mar 14, 1931.